Signals

I made another bad choice of anchorage that night. For reasons I’m embarrassed to admit; instead of crossing the channel at Port Bolivar, heading for the inner harbor at Galveston, which was well protected from wind and wave — because I thought it would be ideal to keep away from marinas and yacht clubs, be cruising sailors not marina lizards. I put us in a really bad spot, in a southeast bite of Galveston Bay.

The cold front coming out of the west was due to blow twenty to twenty-five. I didn’t think the surface chop would be so bad, two to three feet, just a little bumpy. The other choice was to make all the way across the bay, and get in lee of an island on the high side. Piloting there would be tricky, lots of shallow water with privately marked channels, bound to be shifty. You needed local knowledge.

So instead of anything else, I put us in lee of a radio beacon, not a tower. The bulky upper structure did offer some protection from the wind. The steel pylons would help break up the chop before it reached us. Before the wind came, it looked like plausible shelter.

So instead of anything else, I put us in lee of a radio beacon, not a tower. The bulky upper structure did offer some protection from the wind. The steel pylons would help break up the chop before it reached us. Before the wind came, it looked like plausible shelter.

Soon as the sun went down, it got bumpy. Not so the boat was taxed, Mysterion took it like therapeutic massage. Finally a bit of pressure was applied to members devised to hold up in a hurricane.

Betsy, not knowing the boat’s capabilities, never having experienced choppy water, thought we were in danger. As the pitching and rolling increased, she gave off little yelps of fear and wanted me to hold her. Again I was guilty of putting the baby in a rough way. Last night had been much worse to my mind, but I would not speak of it to her, and I did not want to think about it, not being able to change it. Tonight, as I was not worried about the boat rolling over, my confidence had a calming effect on Betsy. She relaxed in my arms and fell asleep finally.

Lying in the aft cabin, it was not a bad ride. The conditions were somewhat uncomfortable, nothing like dangerous, except that I might have anchored farther away from the goddamn radio beacon. I would have settled for more wind and taller chop. I couldn’t sleep, in case both anchors broke loose and we dragged toward the beacon or the shallow water behind us. I had to be ready to jump on deck, cut the anchors loose if necessary, and motor out of there. I kept the engine running on idle the whole night, alert to the swings and pull of the hull against the ground tackle. I wasn’t about to lose the boat under that radio beacon, or be washed up in the shallows.

The steel pylons of the beacon were a nasty sight next morning: crusted with oysters, barnacles, and beards of reddish-brown seaweed. We were close enough to hear the barnacles and oysters gurgle, snap, crackle, and pop, the way they do, like razor sharp Rice Krispies. The sky was gray and low hung. The chop running three to five feet, the wind blowing twenty.

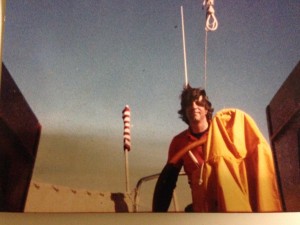

I had to put Betsy at the wheel of the boat. She didn’t want to do it. Scared to touch the engine controls. The motion of the boat seemed wild to her.

“Don’t pay any attention to that. You know how to run the boat in calm water. Just do it the same way and watch me for the signals.”

The boat was in no particular distress. The anchors had hung fast all night. It was going to be a job breaking them loose. I would have to go to the bow and operate the windlass winch. I could not ease the boat forward with the engine, as I needed it done, without Betsy. To retrieve both anchors, we had to pull closer to the beacon.

I needed her calm and able to watch me, to take hand signals. Raising an anchor in heavy chop was tricky. I had never done it in a boat this heavy.

I crawled forward to the pitching foredeck. There I sat for a while, feeling the rhythm of the chop, watching the anchor lines go slack, and then snap bar-tight against strain of the hull. The boat wanted to break loose and fly downwind, away from the beacon, into shallow water. It was not such a bad spot as it appeared. I crawled back to the cockpit and sat down beside the wheel, where Betsy was standing, gripping the wheel for balance on the wallowing sailboat. She had had a rough night, very concerned for the baby; she did not want me out of arm’s reach.

“I’m really scared. I don’t want to do this at all,” she said. It sounded as if she were speaking comprehensively, regarding her romance with yachting. I had the same thought. The embryo in her womb had changed everything.

“We don’t have to do it, Betsy. We can sit here until the wind slows down.”

“How long will that be?”

“About noon.”

Betsy didn’t say anything. She had a hard look on her face.

“We’ve practiced it before, just remember the signals. Go ahead and put the engine in forward.”

“Now?”

I showed her thumbs up.

“All right,” she came back fretfully, “there it is. What do you want me to do now?”

“Put it in neutral.” I closed my hand in a fist and held it in front of her.

“Remember?”

I gave her thumbs up again.

She put it in forward.

Thumbs down, reverse.

“Gimme neutral,” I closed my hand.

“That’s all I have do?”

“That’s it.”

“Are you going back up there now?

“Soon as I drink some milk and eat a chocolate chip cookie.”

“Fuck it, I’m ready,” Betsy said.