Go Home and Build Your House

Soon as darkness fell, I had a craving to sleep. The day had gone by without a nap, and I was feeling the weight. The wind had quit, the ocean was flat calm, and I was running the engine at full power, motoring behind the Dry Tortugas, headed in for Key West.

Just at nightfall, the running lights of distant shrimp boats came on, and I found myself flanked port and starboard by the shrimpers that operated out of Key West, more of them than you could count, strung out for miles.

Each winter, hundreds of shrimpers based in Key West worked the ocean around the Dry Tortugas. There were boats everywhere, so I couldn’t sleep. Even a little bit. Allowing my boat to steer itself while I closed my eyes, even for fifteen minutes, I might run afoul of shrimp boat captain with his gear in the water, crossing his lines and tangling his nets. Colliding with a freight ship, you would be instantly sunk, which might be preferable. I did not want to cross the bow of a shrimp boat captain, so I kept watch.

During the past three nights and four days, I had had a total of five or six hours sleep, maybe. As the night wore on, staying awake was torture. I had never experienced anything like it. I was so sleepy I cried. Which was good, the self-pity energized me with self-loathing.

I tried bending my fingers back almost to the breaking point. That worked, but only as long as it hurt too bad to keep it up. I found that rubbing the back of my head against the steel wire of the backstay helped some, giving myself a headache. I repeated the Lord’s Prayer constantly. As long as I could hear the sound of my voice, even with eyes closed, I was not sleeping, so it seemed.

At some point, a voice I’d never heard before interrupted. It said, “If you repeat that prayer one more time, you’re going to die.”

And I knew it was true, and I believed it. Now fear awakened me, for praying was sedative, it put me in a trance, and while I was in it, the prayer soothed my craving for sleep, which fear interrupted. The voice that threatened was evil, and I believed it, surely knowing I would die if I prayed again.

The bravest thing I ever did was saying to myself, “Hold hands with God.”

I took my own left into my own right, as if God and me were holding hands. I assumed I would die, and prayed anyway, and the fear left me.

The moment of decision having passed, the threat of death seemed imaginary. The voice that delivered the threat had left its echo. There was no more craving to sleep. My life was pregnant with choices. I no longer trusted myself to judge what was possible. All of my designs looking forward were suspect. To father children with a breeding partner I sort of loved, was not in love with, having bound myself in marriage and conceived a child, I now wondered if I’d gone too far when I took the first step.

The sunrise was washed out, colorless gray-white. The north wind was colder. The choppy ocean felt heavy under the boat. I was impatient to be anywhere that was not constantly moving. Having gone four days with little rest, the slightest exertion irritated me. I sat on the coach roof of Mysterion, rigging dock lines and fenders. I would not stay long in Key West, where broken dreams spilled into the streets each morning when the bars shut down. I knew Key West from years ago, remembering winter sunshine that made promises it never kept. Key West swallowed people, swept you away on a tide of beauty’s gastric acid, lovely to swim in until you noticed you were dissolving.

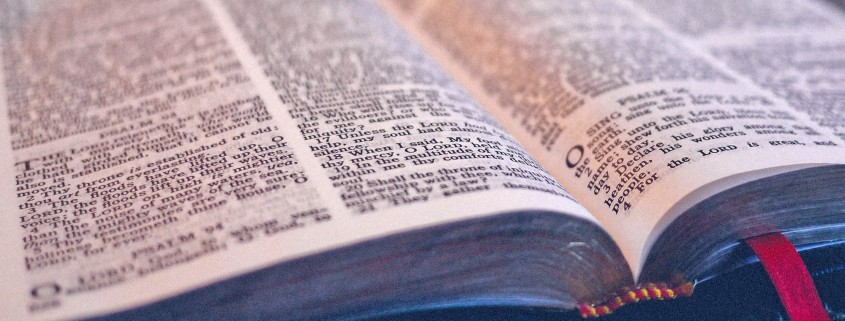

I hunkered down behind the canvas dodger, out of the wind, holding a damp Bible. The cover blew open, pages rustled and flipped. I read as though the Book of Jeremiah were speaking directly to me, the first three chapters, large with purpose.

My rational mind observed these thoughts with a smirk. Was I so desperate to know myself, so confused that a book full of miracles blown open by the wind could seem as solid as a manmade chart of the ocean? Was I mesmerized by lack of sleep? Or did I perceive clearly, as I believed I did, that I was not alone on the boat, that I had not been alone at sea for an instant.

The voice of authority that had preserved me across the Gulf of Mexico, said, “Go home and build your house.

What did that mean?

I had no affinity for the town I had been born to; I’d left Myrtle Beach when I was seventeen. The life I’d been trained to live was far behind me. I had no desire to raise children in a carnival town.

“Go home and build your house,” I said to myself, trying to imagine the geography of home, the physical structure of a house. My sense was that “Home” and “house” were not the same entity. And I did not know where to look for either one.